Beyond the House

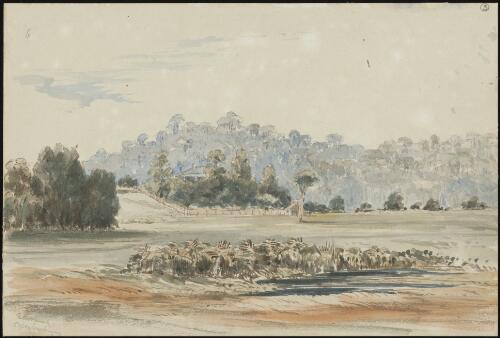

Garranbinbilla, now known as Newstead Point, was a centre of farming, resources and community, long before the first European settlers arrived. The shallow waters and sand banks of the creek enabled easy crossing from one side to the other, and Garranbinbilla was a place for tournaments and combat training.

Major Aboriginal camps were well-established on the banks and hills, and the creek was a main source of shipworm (called cobra, canyi or kunyi). Aboriginal fishermen and women placed mounds of casuarina logs in the water to attract the worm, which in turn attracted an abundance of fish. They set fish traps and used tow rows (hand woven nets), catching so many that they were able to supply most of Brisbane’s residents with fish well into the 1860s. During the city’s development, many Aboriginal families were integrally involved in the city’s river-based industry.

After the arrival of European settlers, Breakfast Creek became a site of extreme violence and conflict as settlement pushed into Aboriginal lands. By the late 1840s, an increase in European farmers in the area meant Aboriginal pathways were becoming busy roads and farms were impinging on land that was used for hunting, harvesting and fishing, and fresh water supply. Hostilities grew, and multiple raids, retaliations and violence took place between the settlers and Aboriginal communities primarily between the 1840s and 1870s.

Newstead House thanks Dr Ray Kerkhove for his extensive research into First Nations life at Breakfast Creek, and to Aunty Raelene Baker for sharing recollections of life at Breakfast Creek from her family and community.

A volatile environment

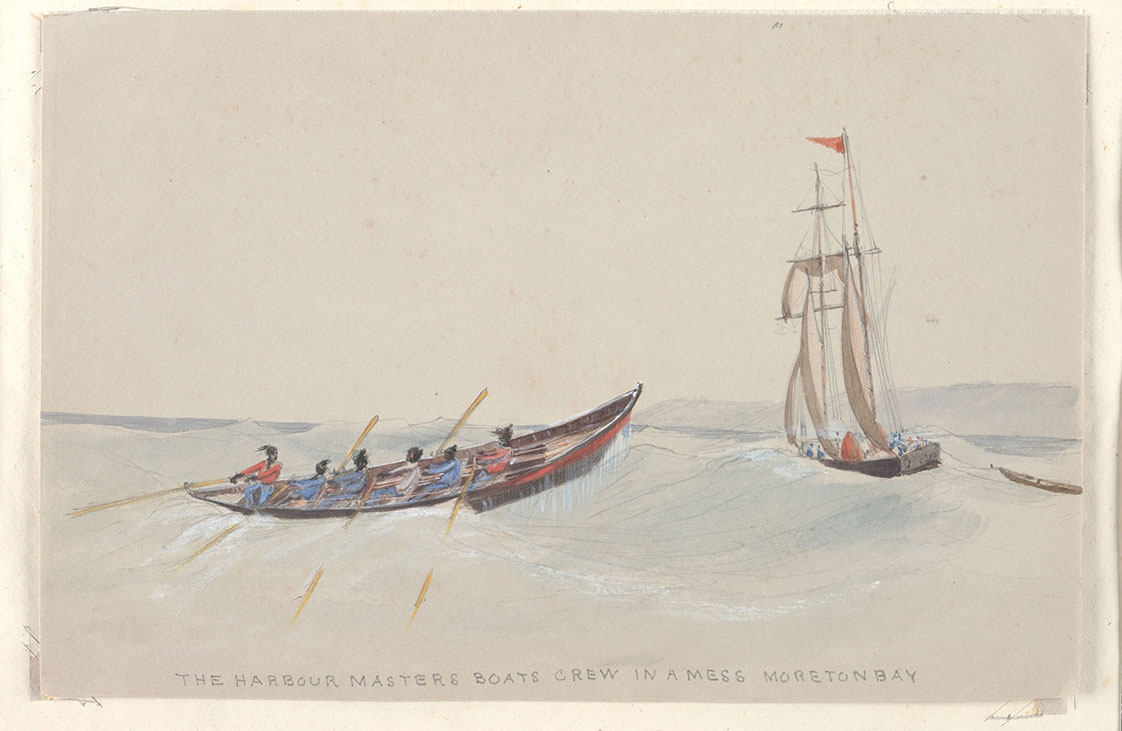

The social, political, and economic environment was volatile and quickly changing during the early years of the European settlement, with Newstead at the centre.

In 1850, all settlers in the Breakfast Creek area sent a petition to Sydney demanding police protection from the local Aboriginal people. The Traditional Owners were chased out of the city every evening and on Sundays, despite selling goods, working, and travelling into the city by day for government-organised events such as yearly blanket distribution days outside Captain Wickham’s Police Magistrate’s Court.

As Captain Wickham owned the land on which the main Hamilton camp stood, the Newstead site became a centre of Aboriginal-settler conflict. Between 1842 and 1870, police and settlers six times burnt down the Aboriginal camps at Breakfast Creek and Hamilton, destroying all food and belongings. Such actions were conducted under Captain Wickham’s authority.3 Even at the time, this resulted in considerable outrage across Australia, placing Newstead House at the centre of public controversy.

Aware of the significant role Newstead played in the town’s social and political life and especially its policing, Aboriginal leader Dalaipi and his relative, Dalinkua, based themselves at the Breakfast Creek camp directly opposite the house. While there, they arranged for the publication of a series of powerful indictments in The Moreton Bay Courier between 1858 – 59. These described the hypocrisy of the Christian settlers’ treatment of Aboriginal people and were some of the earliest statements in Australia to be authored by First Nations people.

At this time, the Moreton Bay colony was pushing for separation from New South Wales, which was officially achieved in 1859. Despite having advocated for the separation, Captain Wickham’s position as Government Resident was not required in the new Queensland Government, and his requests for a government pension were denied, leading to the Wickhams vacating Newstead and Australia forever in 1860.

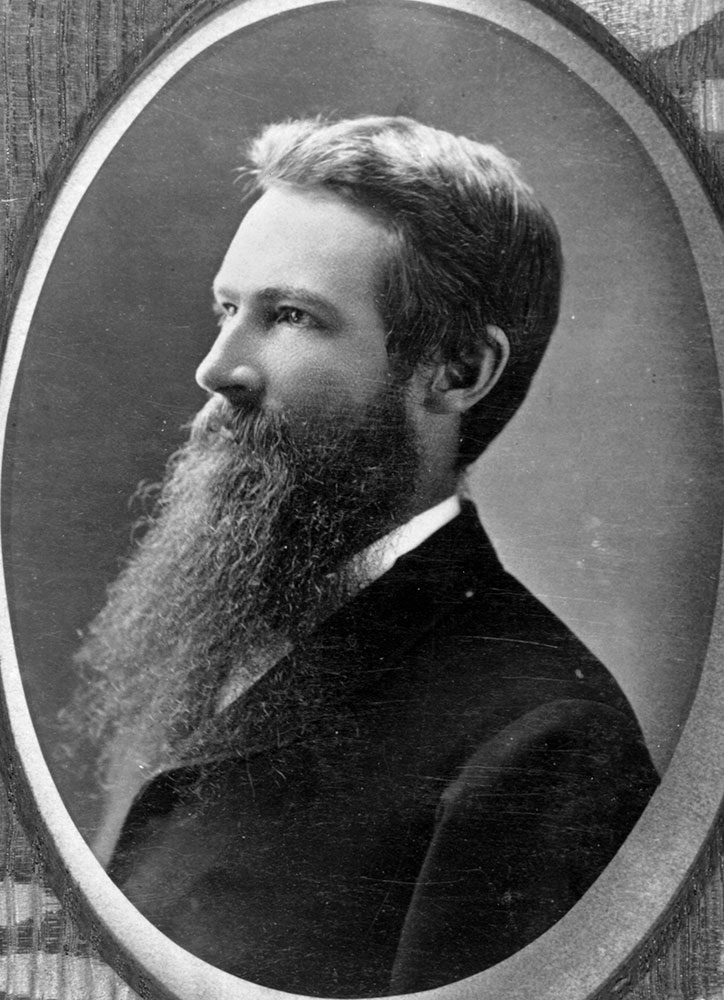

Newstead’s role as a social and political centre continued with the Harris family, whose party guestlists boasted names like Sir Samuel Griffith, Queensland’s Attorney-General, Premier and later Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia. George Harris himself entered politics, appointed as member in the Upper House of Queensland’s first parliament, and the Consular Agent in Brisbane for the King of Italy, resigning from both positions after his company’s insolvency in 1876.

The economic situation became precarious towards the end of the Harris family’s time in the house. A global economic depression took hold in the 1870s, and politics would continue to change over the next decades, with the Australian banking crisis in 1893, the Boer War, and the federation of the Australian states in 1901. These external factors, as well as George Harris’ business decisions, would ultimately culminate in the Harrises losing Newstead and the glamorous opportunities for socialising.

Explore

3 Adjacent Rooms

Click on a room to find out more